| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Last Updated, August 2015

|

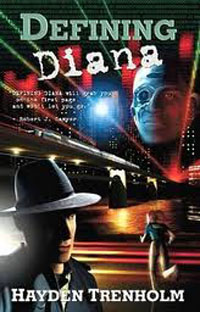

by Hayden Trenholm Bundoran Press 2008, 285pp. $20.00 Hayden Trenholm's Defining Diana starts with the classic locked-room mystery: a murder victim is found in an apartment locked from the inside with no obvious signs of break-in or struggle. To this classic "Who done it?" (and "How was it done?") Hayden adds the additional element of "Who was the victim?", and it is this latter mystery that gives us the book's title: there is no trace of Diana in any of the usual databases, so who was she, and how did she become so nearly invisible? In spite of the title, however, relatively little of the novel is actually devoted to solving this opening mystery. Partly, this is because other, more pressing cases intrude; and partly this murder is only one clue pointing to the larger conspiracy in which the characters ultimately become entangled. The real purpose of the title, then, is not to highlight the initial murder, but to underline the central theme of the novel: the search for identity in a time of rapid technological and social change.

|

But Frank is not the only one facing an identity crisis: Frank's second in command is reeling from the sudden departure of her long time husband, trying to figure out who she is, what went wrong, and whether she should allow herself to date Frank, another colleague, or just go it alone. Another detective is torn between his loyalties to the police and his identity as a cyborg, since leading members of his subculture appear implicated in Diana's murder. Yet another officer is struggling with his slow descent into psychosis. The general collapse of the norms, values, and relationships that Canadians once took for granted are symbolized by the dissolution of Frank's team, both as individual psyches, and as a unit -- the Chief shuts down Frank's department half way through the novel. Indeed, the only one in the book who appears content with his identity is a particularly odious criminal who keeps cropping up as one of "Mr. Big's" accomplices.

On the surface, the central mystery revolves around a case of identity theft, but thematically, Hayden makes it clear that it is not just Diana and the other murder victims whose identities have been erased. Everyone in our post-modern world, Hayden seems to argue, has had to compromise some part of who they were to accommodate to the new corporate order. The private security guard who discovers he has lost his father's Sikh roots, and the CISI agent who goes so far under cover he loses everything that matters to him, are just as much victims of identity theft as those who have been erased from the databanks or killed.

Thematically, then, Defining Diana is a complicated and largely successful novel. It is, ironically, the surface story that has problems.

First, although I accept the Mike Hammer style clichés as a necessary part of Frank Steele's characterization — the whole point is that as he struggles to redefine himself, all he has to drawn on are the ready-made stereotypical identities presented in the mass media — the reader still has to wade through an awful lot of hard-boiled detective dialog. Fans of that genre may well find these constant allusions familiar and amusing, but struck me as painful and distracting. Similarly, the constant shifts between Frank Steele's first person narratives (wholly in keeping with his character) and the third person narratives of the other characters felt like cheating to me. The traditional first-person detective narrative limits the reader to protagonist's perspective — the reader knows what the protagonist knows, and nothing more. But here, every time Frank is left wondering about another character's motivations, we turn the page, and there it is spelt out for the reader in their chapters. The novel might have been a stronger mystery had it all been written from Frank's perspective, though that would admittedly have made it a much harder for Hayden to depict the other character's identity crises.

Second, without getting too specific (no spoilers!), I did find the science in this SF mystery to be a little shaky. Hayden doesn't — quite — invoke being bitten by radio-active spiders, but the explanations are almost that pat. I would have liked a little deeper exploration of the philosophical and scientific issues involved in self, identity, and consciousness than are delivered here, especially given that this is otherwise such a philosophical work. And it's just a little hard to accept the evil-scientist-with-secret-underground-laboratory motif as a framework for a serious exploration of anomie.

Third, there is an underlying unpleasantness about much of this mystery. Although not exactly splatter punk (the worst gore happens off stage), the crimes are frequently gruesome and leave a bad taste (as was no doubt intended). Furthermore, none of the protagonists are very likable, though one does end up with a grudging respect for those that manage to draw a line in the sand, and so define themselves by saying, "this far and no further". But, even so, I wouldn't want to have coffee with any of them.

Overall, I would give Defining Diana a cautious recommendation: fans of CSI or Mickey Spillane probably won't share my reservations with the surface narrative, and the underlying exploration of identity is satisfyingly thought-provoking. Hayden Trenholm is to be commended for undertaking such an ambitious literary novel, and Bundoran Press congratulated for supporting another important voice in Canadian SF. Kudos also on Dan O'Driscoll's cover — what you see is exactly what you get.

Reprinted from Neo-Opsis Magazine #16 (Winter, 2009)

P.S. Hayden was not overly pleased by this review, and responded by writing me into the sequel, wherein he had me killed and eaten. (Not by name, you understand, but I had already suspected it was directed at me when he voluntarily confessed the fact to me sometime after.) This is, of course, a professional hazard of being a reviewer, and one of the great perks of being an author. Since then, Hayden has bought Bundoran Press and become one of the country's great SF editors as well as continuing his own writing career.

Hayden Trenholm

Hayden Trenholm