| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Last Updated, Aug 2010

|

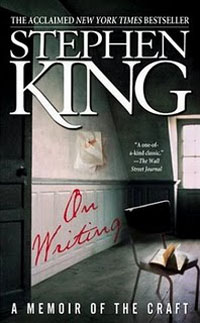

A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King Pocket 297pp. Two-thirds of the way through my first novel, I felt the need for a little moral support, so ordered a shelf of books on writing from Amazon.ca. This one happened to be on top of the stack when I went on holidays and needed something for the plane. The book quite surprised me: the first 94 and last 19 pages are in fact autobiography, which is certainly not what I expected from a book on writing. It's largely a pleasant surprise because this is Stephen King after all, so as autobiographies go, it's pretty slick. And it does rather support his contention that one must write what you are. A central theme of the book, once King gets around to the actual "how to write" section, is that one must "write the truth", by which he means, in part, "write what you know." Thus, the "CV" portion of the book serves as back-story to demonstrate where Stephen King the writer came from; and, perhaps, even to go some distance towards answering that perennial question, "where do you get your ideas?" There are some quite compelling insights here, including the revelation that "The Shinning" was likely a call for help during his own losing struggles with alcohol and drugs (p. 89). (King subsequently (p.92) directly addresses the Hemingway stereotype of the creative genius as necessarily a drunkard, and makes a compelling case that this is a literary creation without basis in reality: the two conditions are unrelated.) |

But that one aberration aside, just about everything else King has to say resonated strongly with me, not only as a writer, but also as an instructor. For example, he devotes quite a few pages to the need to finish a first draft before showing it to anyone else. I have experienced, and frequently observed in colleagues and students, the death of stories or articles critiqued too soon. Rough drafts are often that, and not everyone can look at one's initial attempts and see the potential it could have once properly revised and polished. It's all too easy for a casual observer to dismiss a rough draft as "not very strong" or complain that the "ideas just doesn't make sense". And often the author will look at what they have so far, see the holes that have just been pointed out to them, and give up. But this misses the point that first drafts are always weak. This is particularly a problem with my grad students, who constantly compare their own tentative first efforts against the finished product of others' published articles/stories. They don't realize that that published story/article they are using as the standard went through eleven drafts, four colleagues, and an editor to end up like that. The initial draft of those now successfully published pieces might well have been much, much worse than what they currently have on their own screen. But never having seen anyone else writing (writing being largely a solitary act), they often assume that writing comes easily to everyone but them, and that if their first draft is this weak, then they might as well just give up on this story/article.

For King, the secret is putting the completed manuscript away for six months and to work on something else entirely, so that one can return to it with fresh eyes, completing the rewrite from a more detached perspective. I completely agree. But that's not always possible for grad students working against the deadline for thesis completion. Nevertheless, I encourage students to keep moving forward to finish the full first draft all the way through before revising anything, because (a) by the time they get to the end, they will have gained at least a little distance on the earlier chapters, which aids in spotting needed revisions; (b) there is no point revising something to a high polish early on, only to discover that that section has to be fundamentally changed, deleted or replaced when one gets to the end and realizes that's not where they needed to get to in the end; (c) after one has a complete draft and sees how it all kind of hangs together, our egos are better positioned to hear constructive feedback Š the project is less fragile than in the early stages when one's ideas are still quite tentative and one's ego vulnerable; (d) pragmatically, one has a better chance of passing with a weak but completed thesis than with the first three brilliantly refined chapters of an incomplete thesis. Another point on which I largely agree with King is his reservations about writers' workshops. I think these can be invaluable if handled correctly, but too many are as he describes them: too vague feedback on too early drafts:

-

How valuable are [these daily critiques]? Not very, in my experience, sorry. A lot of them are maddeningly vague. I love the feeling of Peter's story someone might say. It had something...a sense of I donÕt know...there's a loving kind of you know...I can't exactly describe it.

Other writing-seminar gemmies include I felt like the tone thing was just kind of you know; The character of Polly seemed pretty much stereotypical; I loved the imagery because I could see what he was talking about more or less perfectly.

And instead of pelting these babbling idiots with their own freshly toasted marshmallows, everyone else sitting around the fire is often nodding and smiling and looking solemnly thoughtful. In too many cases the teachers and writers in residence are nodding, smiling, and looking solemnly thoughtful right along with them. It seems to occur to few of the attendees that if you have a feeling you just can't describe, you might just be, I don't know, kind of like, my sense of it is, maybe in the wrong fucking class.

Ouch! But all too often, uncomfortably close to the mark. I've been in some excellent writer's workshops where the attendees are more articulate and helpful than those depicted by King, or where the facilitator has intervened with probing questions to draw out more specific and therefore more constructive feedback from attendees. But I have grown increasingly skeptical about weekend or week-long retreats that consist of a random selection of aspiring writers, most of whom may not 'get' one's particular genre or style or intention; and where the timeframe between first draft and first reading is too close to be useful.

I think one requires a longer timeframe: Where one has a chance to draft, rewrite a couple of times, put the story away for a month or two, then revise again, and only take the story to the 'focus group' once it's ready to be published, just as a final check. For that, one requires an ongoing writer's circle, a small group of reliable reviewers (writers, editors, trusted readers) who can provide clear, concise, specific advice. A few writers who live in large urban centers may be able to develop a circle of such colleagues that physically meets in someone's home on a regular schedule; but more likely itÕs a group of correspondents in other locales to whom one can send the manuscript when it is ready. (And it's a lot easier to dump a correspondent who doesn't work out Š you just stop sending them your stuff as often Š than it is to fire someone from a circle that meets physically.)

But back to King. I found On Writing an invigorating read because the personal anecdotes provide a context that successfully changes the tone of the book from the didactic of the typical "how-to" manual, to a much more involving 'discussion' of the writing life. Although the book cannot directly critique my manuscript, I often find the most useful aspect of writers' workshops is just the validation of the writing life that comes from hanging with others who take writing seriously. Of course, reading On Writing is not really the same as hanging with Stephen King, but then, getting King to accompany me on the plane would have been a lot more expensive, and a lot less convenient, than just ordering the book from Amazon. So a recommended read.

Reprinted from I'm Not Boring You, Am I? July 24, 2009

Stephen King

Stephen King